I’ve taken a bit of a detour this week to explore broader discourse around the electromagnetic spectrum. Obviously this is a HUGE topic so I am only scratching the surface but there are a few things I have found fascinating.

I am interested in how the electromagnetic spectrum is classified as a limited natural resource. This seems at odds with how it is perceived as ubiquitous – or not even considered – in contemporary culture that is built on technologies that rely on it. Similarly, the communication and connectivity that spectrum provides is intrinsically linked to cultural and social values, but it is more commonly treated as an economic and technological commodity.

Sharing spectrum

The full electromagnetic spectrum ranges from gamma rays to radio waves, and the part of that range with frequency range from 30 Hz to 300 GHz makes up the radio spectrum. Different parts of the spectrum have different qualities so are allocated to different uses.

Basic examples are:

-

- Higher frequencies are shorter radio waves that carry more information.

- Lower frequencies are longer waves that carry less information.

- Lower frequencies travel close to the ground and are generally used by the military.

- Higher frequencies travel at greater heights reaching orbiting satellites.

Because of the different characteristics of different frequencies, there are a range of factors involved in how the spectrum is used, shared, exploited, and constrained over time and space.

“The same frequency can be used in different geographical areas, depending on its propagation characteristics; or the same frequency can be used in the same area, but at different times. Or two different frequencies can be used in the same area at the same time…. the cardinal constraint on the use of the radio spectrum is interference-interference with someone else’s use by communicating on the same frequency at the same time and the same place.” (Herter, p. 655)

Renewable and pollutable

Similarities and differences are drawn between spectrum and other natural resources like water, trees, minerals, and air. As such, “ecological equilibria exist for this resource just as they do elsewhere in nature” (Ryan).

A significant difference between spectrum and other natural resources is that it is instantly renewable.

“Unlike hard minerals or petroleum, the electromagnetic spectrum is not depletable; it is always available in infinite abundance except for that portion which is being used. When that portion of the electromagnetic spectrum is not in use, it is instantly renewable.” (Herter, p. 653)

However, a strong similarity is that it can be polluted, wasted, or abused, and it is frequently subject to overcrowding causing interference that prevents it being used effectively.

“The spectrum has been called a “limited” natural resource because, given present technology, there is only a finite portion available for beneficial uses at any one time.” (Herter, p. 655)

Another element at play is that as demand for radio spectrum increases, technologies are developed to use it more efficiently by operating at higher bandwidths.

Global Commons

Gregory and Taylor’s research brings together a range of perspectives on the “constantly morphing policy puzzle” of radio spectrum from around the world to create an interdisciplinary dialogue around radio spectrum:

“Spectrum policy is a field on which academics – especially in the social sciences and humanities – often fear to tread. But why? The current policy climate surrounding spectrum policy will clearly benefit from what the arts and humanities have to offer.” (Taylor and Middleton, p. 8)

They challenge the power dynamics in current approaches to access and affordability of mobile communication with a reminder that spectrum is a public resource. However, “Instead of recognizing this resource as such, the United States and countries in Europe relegate the management and supervision of this natural resource to technocrats who deal with telecommunications.” (Ryan)

In New Zealand, an agreement has been reached for management of the spectrum to be shared between government and Māori partners after a decades-long debate over spectrum rights.

Māori groups consider spectrum a cultural more than technological phenomenon: one that is intrinsic in supporting language and culture just as much as economic development. It is therefore regarded as ‘a taonga, a treasure’” (Joyce, p. 25)

Zita Joyce writes: “the story of New Zealand radio spectrum is about the limits of the property rights regime. More fundamentally, it is about the right of the state to create property rights in previously unpropertized resources, and the right of Indigenous peoples to challenge this propertization, posing traditional forms of knowledge and resource use against state discourses of technology and material value.” (Joyce, p. 38)

Australian spectrum allocation

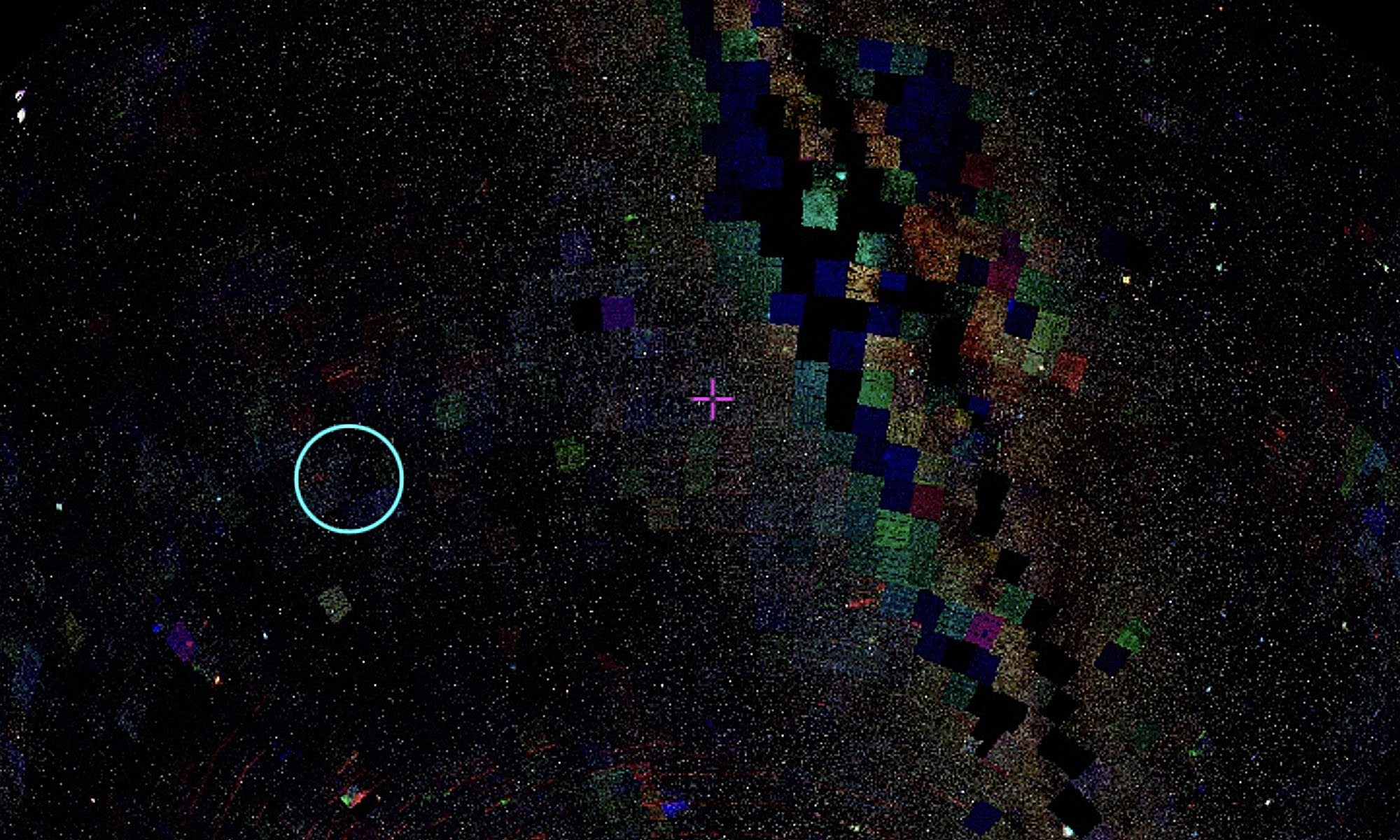

Spectrum in Australia is managed by the Australian Communication and Media Authority (ACMA) and primarily licensed through auctions.

Their Register of Radiocommunications Licences shows who uses which frequencies where, which is what led me into this rabbit hole in the first place, so I am going to write about this in a separate post!

References

Joyce, Zita. “Radio spectrum as Indigenous space: Property rights and traditional knowledge in New Zealand’s spectrum.” Frequencies: International spectrum policy (2020): 19-45.

Herter Jr, Christian A. “The electromagnetic spectrum: A critical natural resource.” Nat. Resources J. 25 (1985): 651.

Ryan, Patrick S. “Treating the wireless spectrum as a natural resource.” Envtl. L. Rep. News & Analysis 35 (2005): 10620.

Taylor, Gregory, and Catherine Middleton, eds. Frequencies: International Spectrum Policy. McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP, 2020.