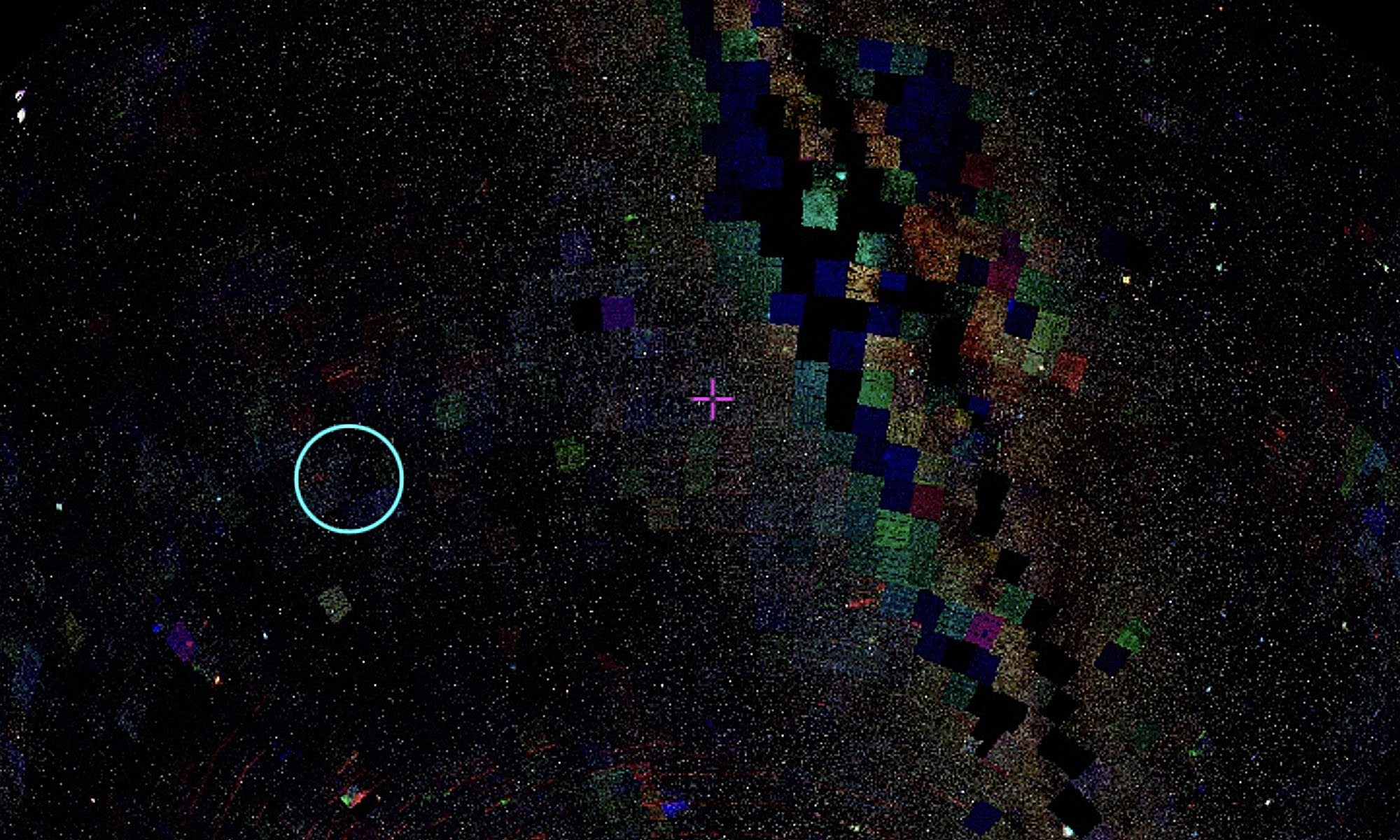

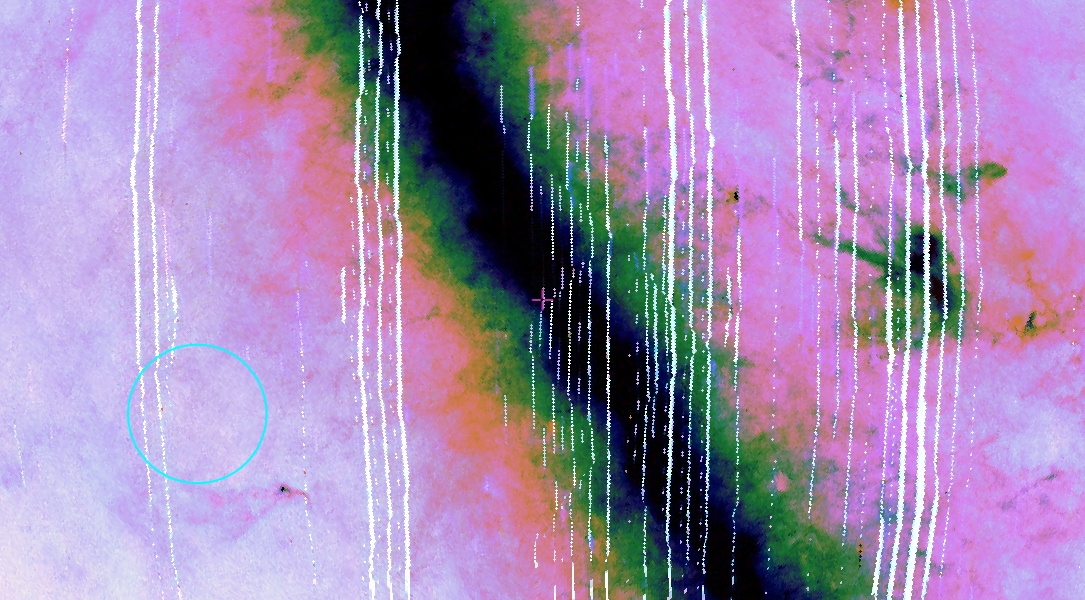

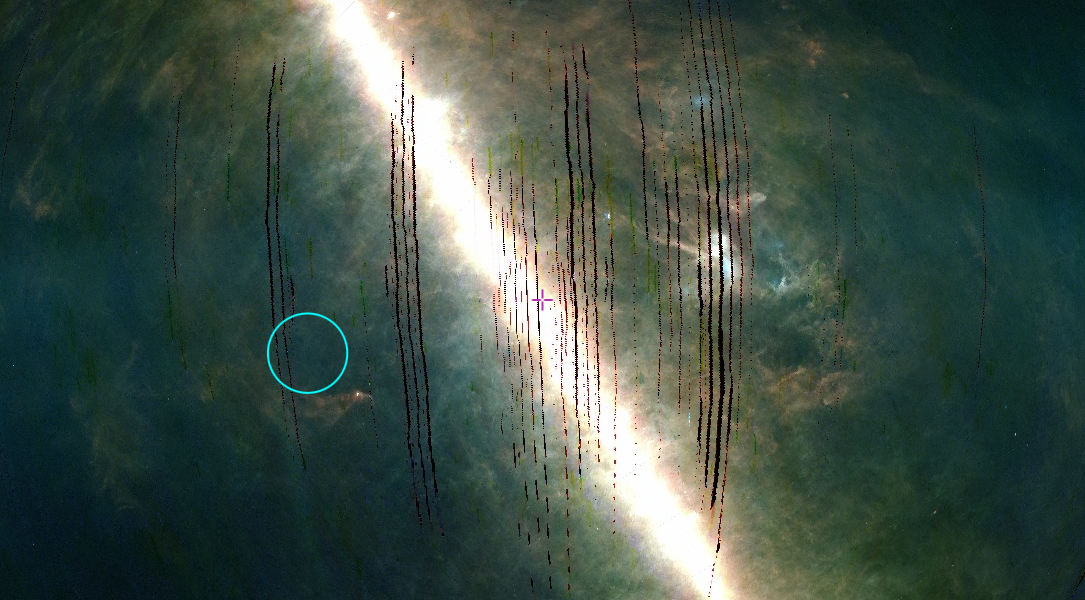

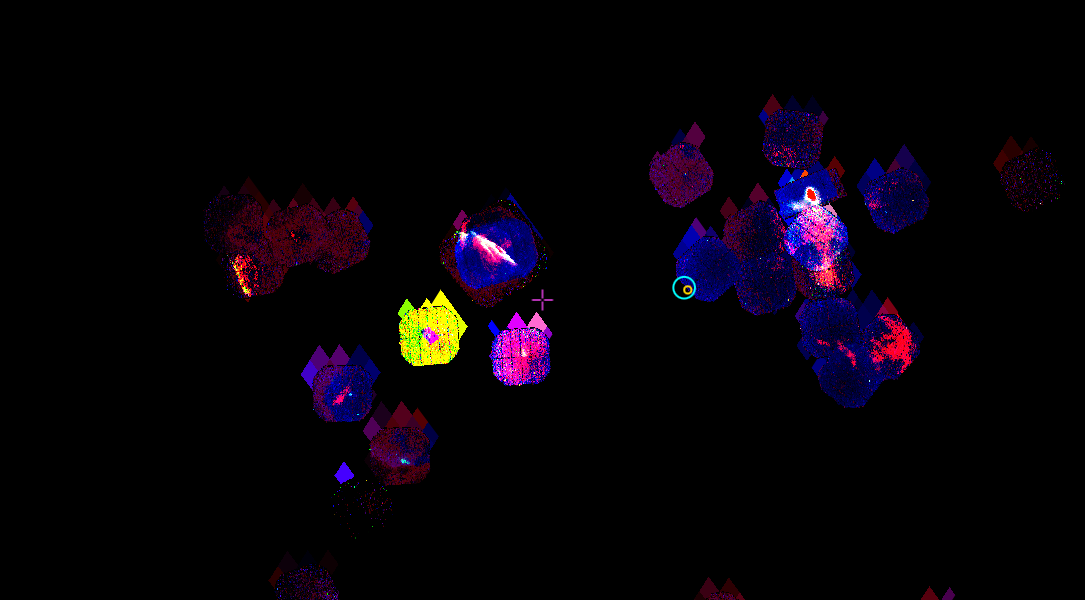

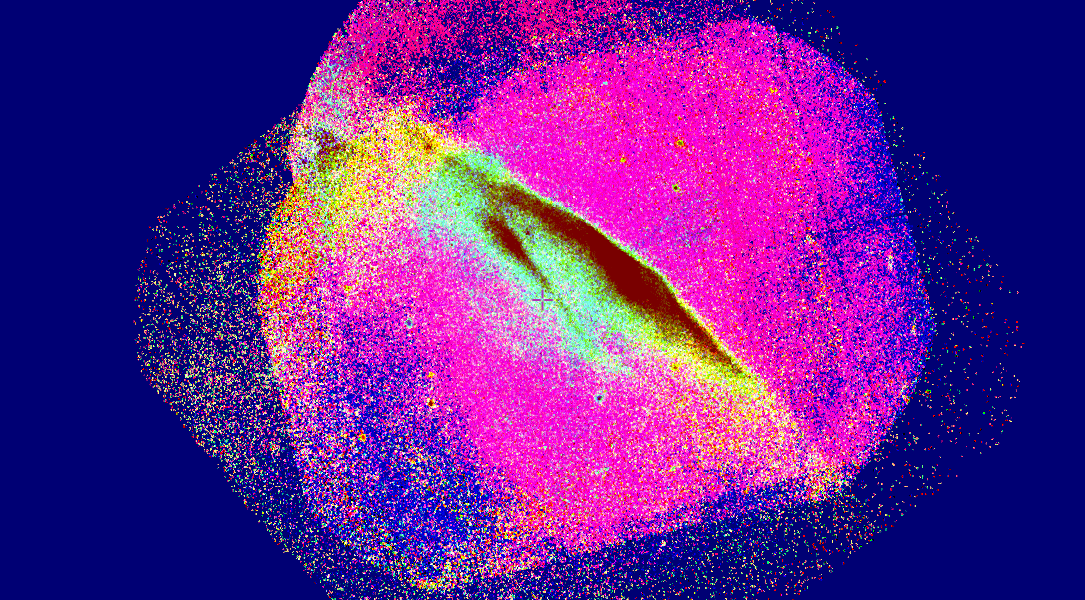

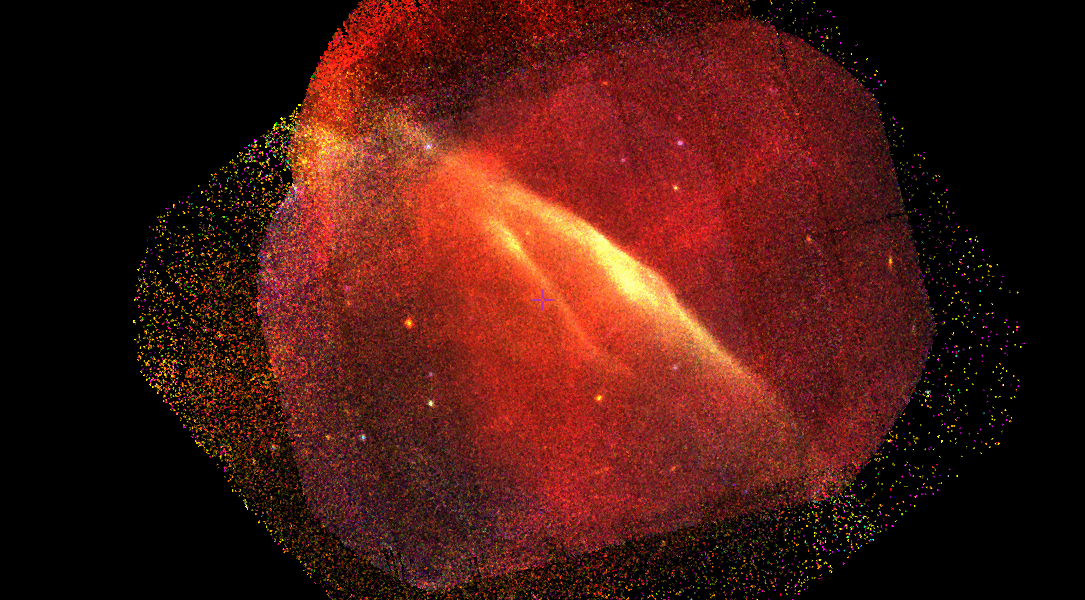

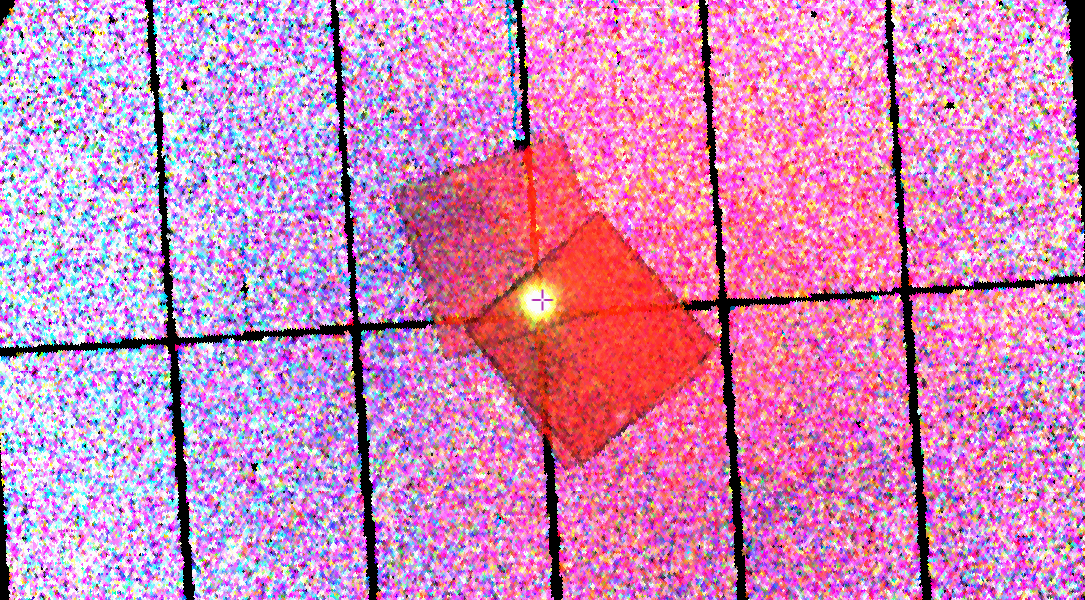

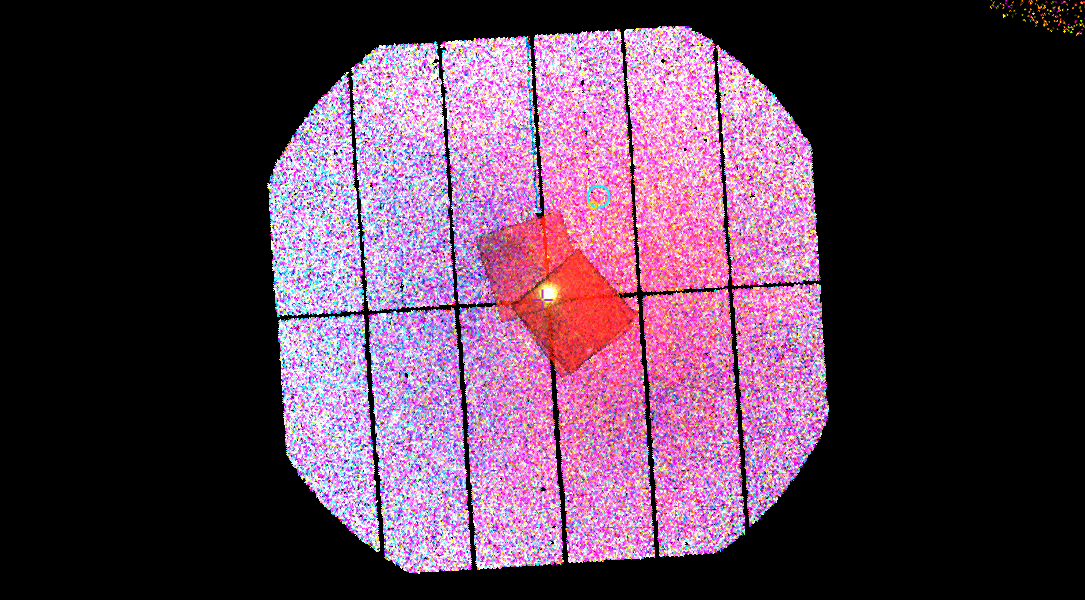

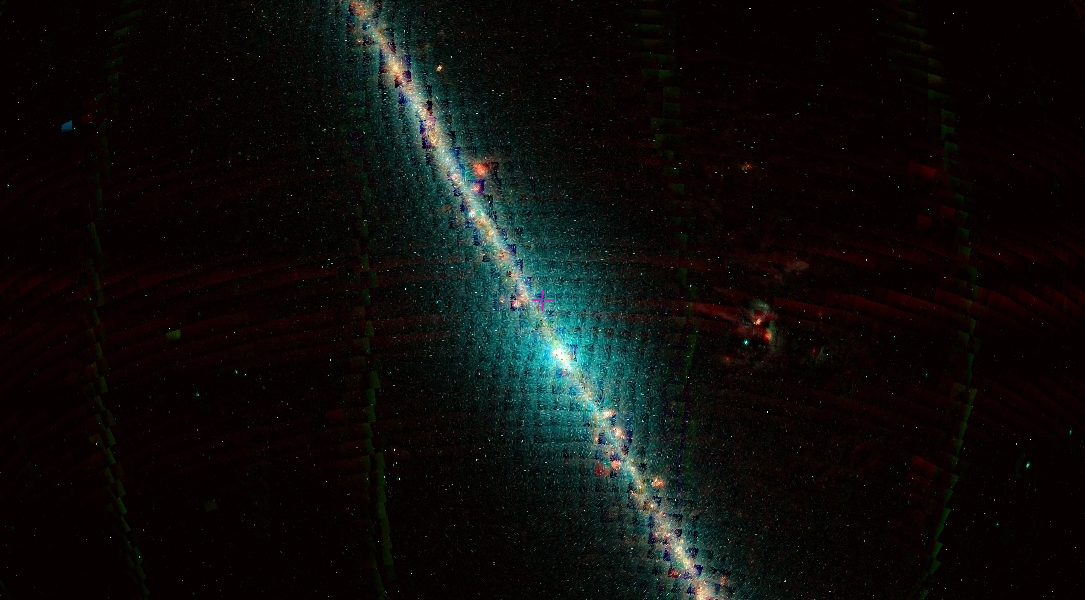

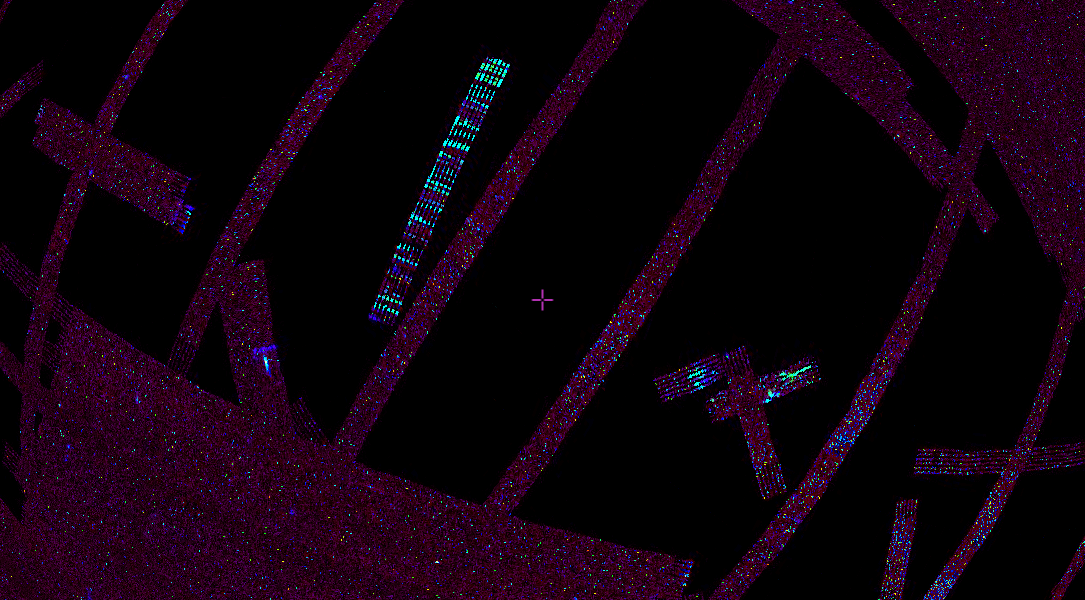

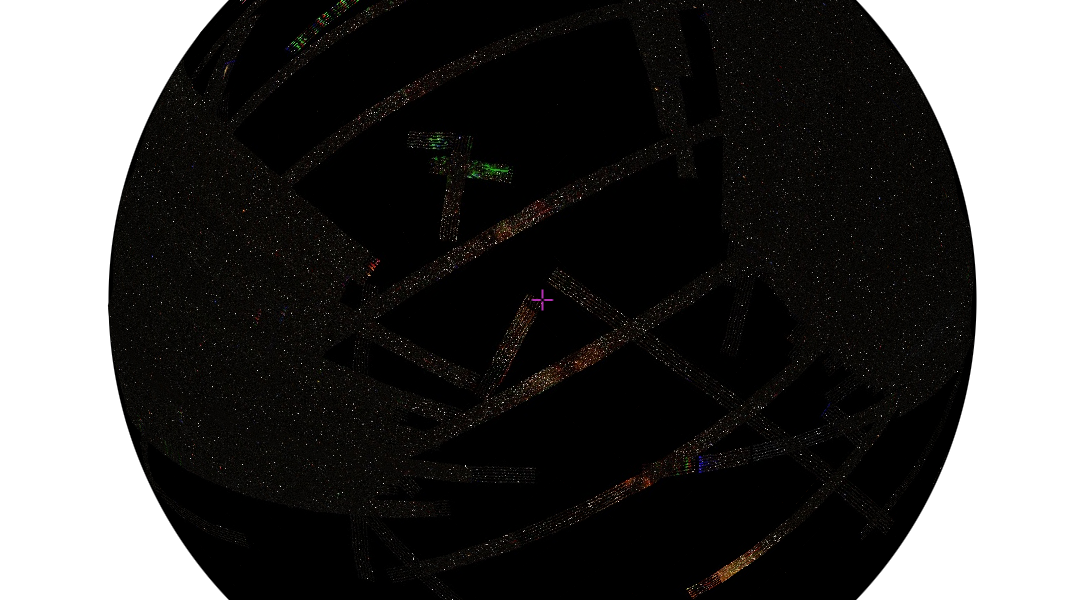

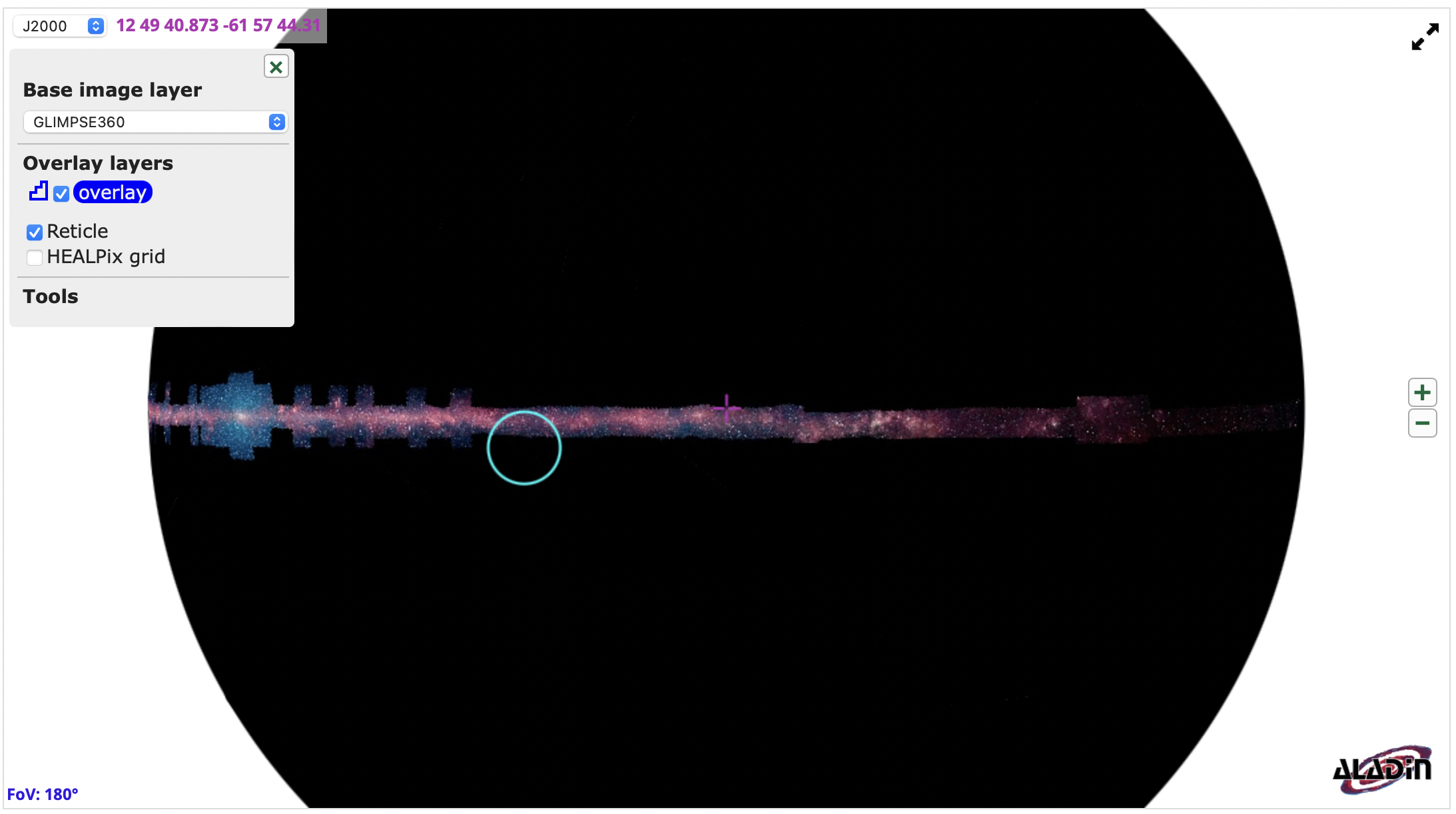

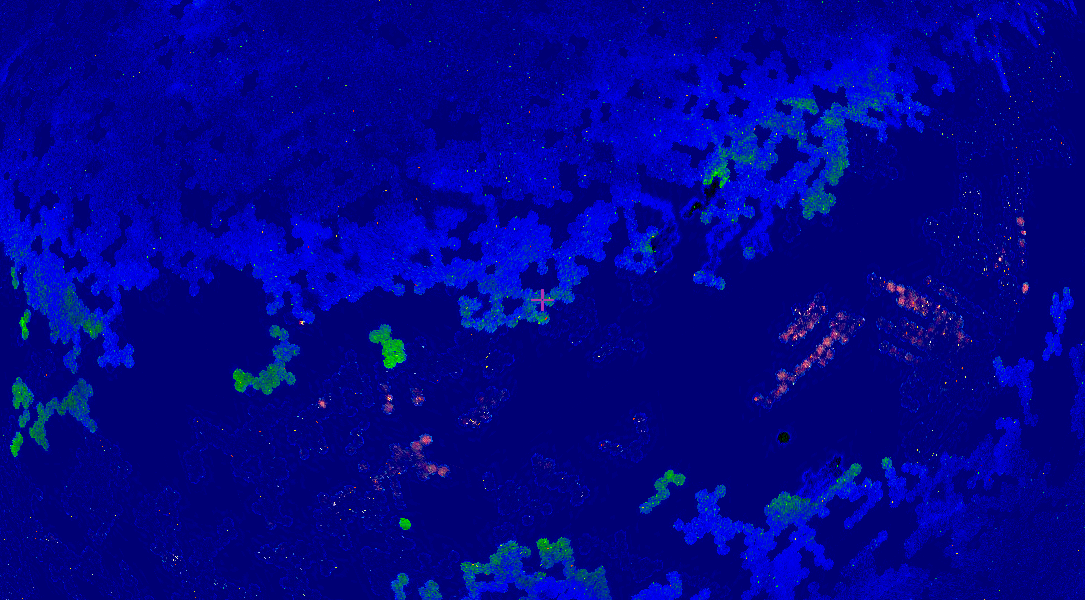

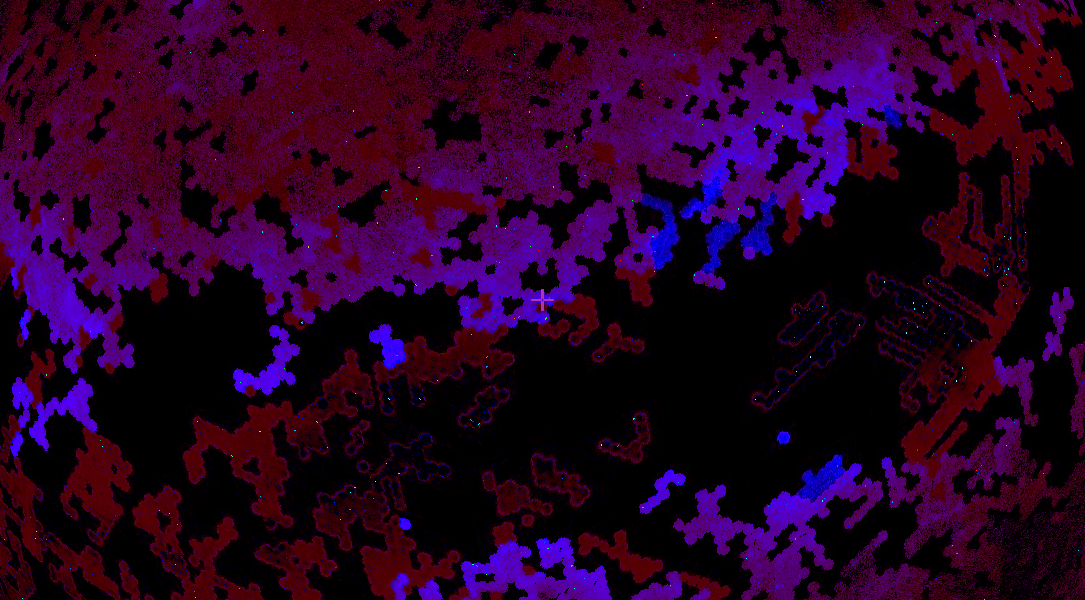

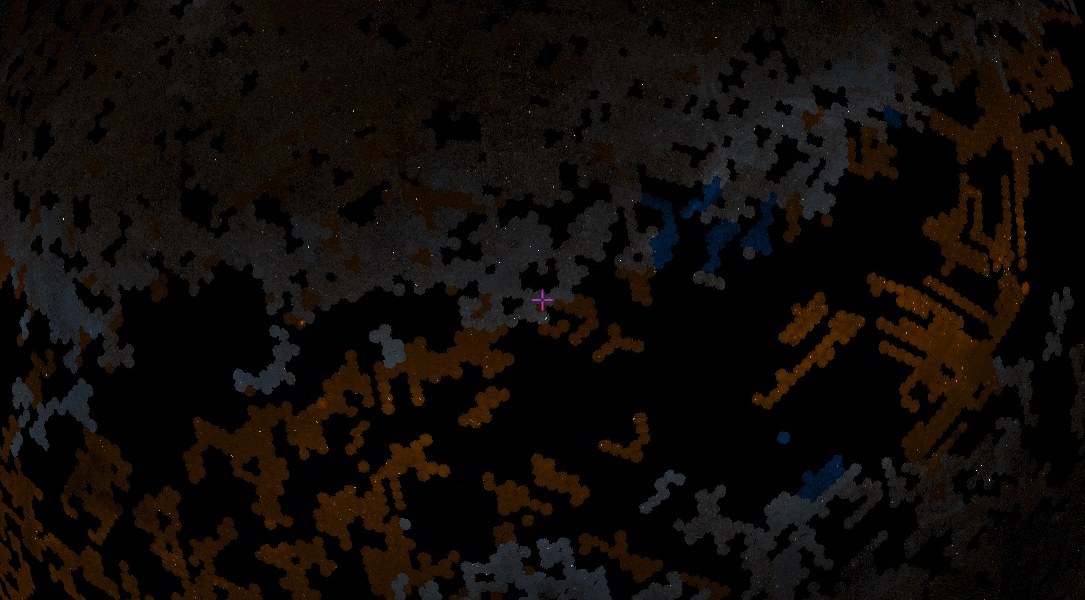

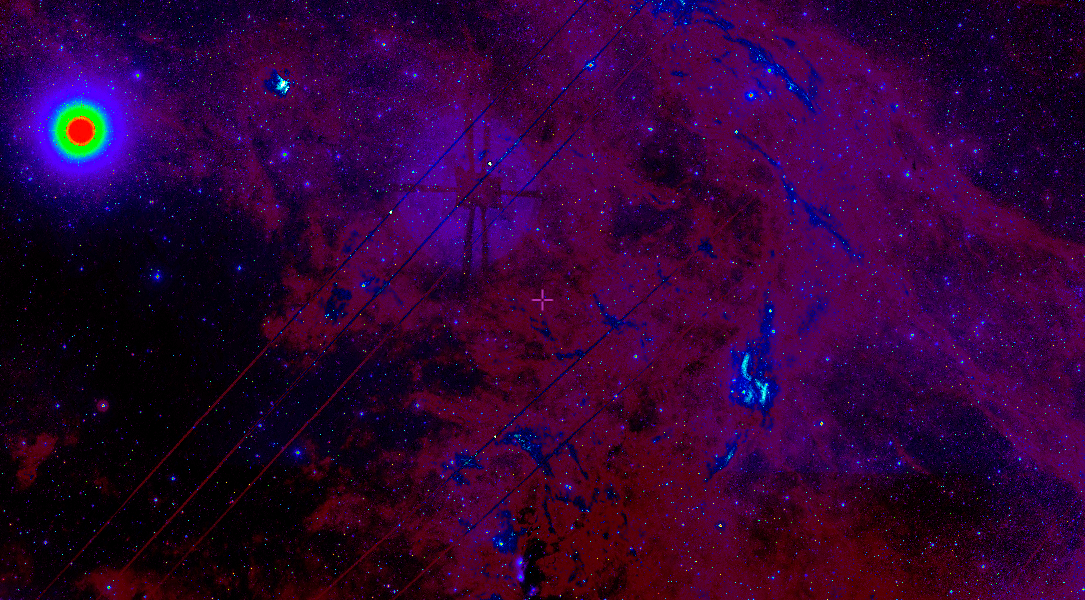

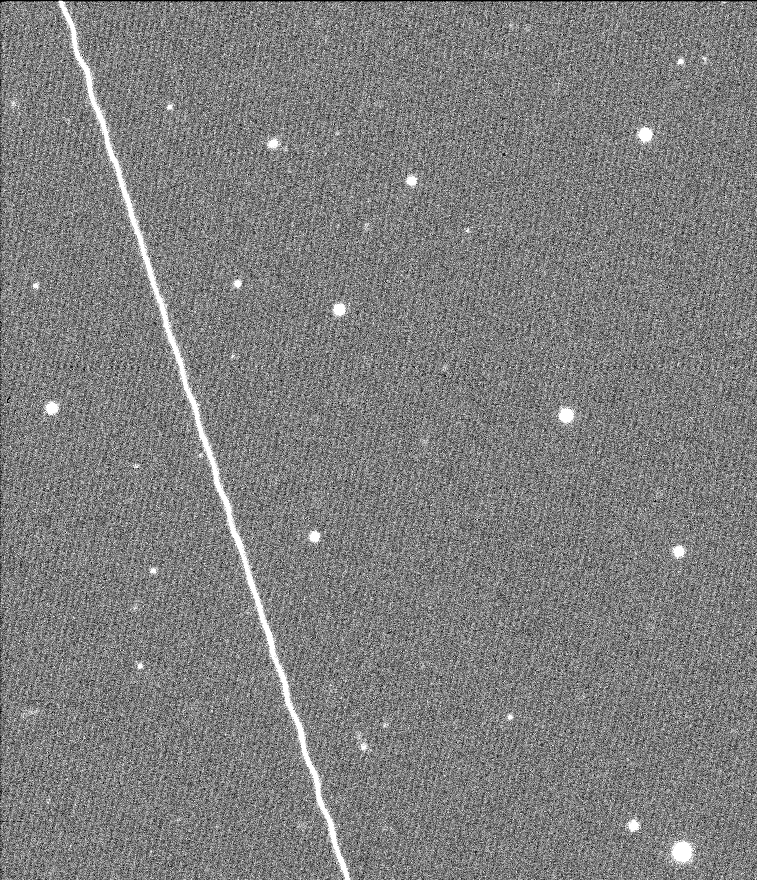

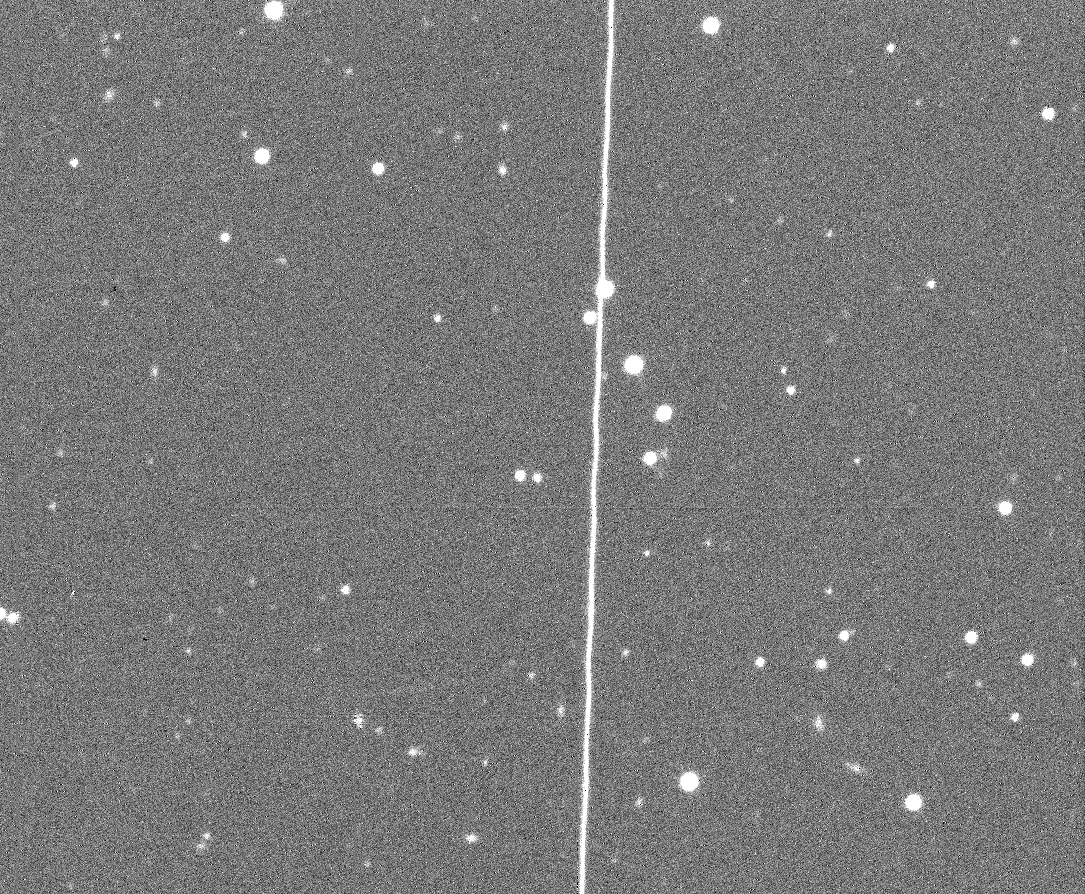

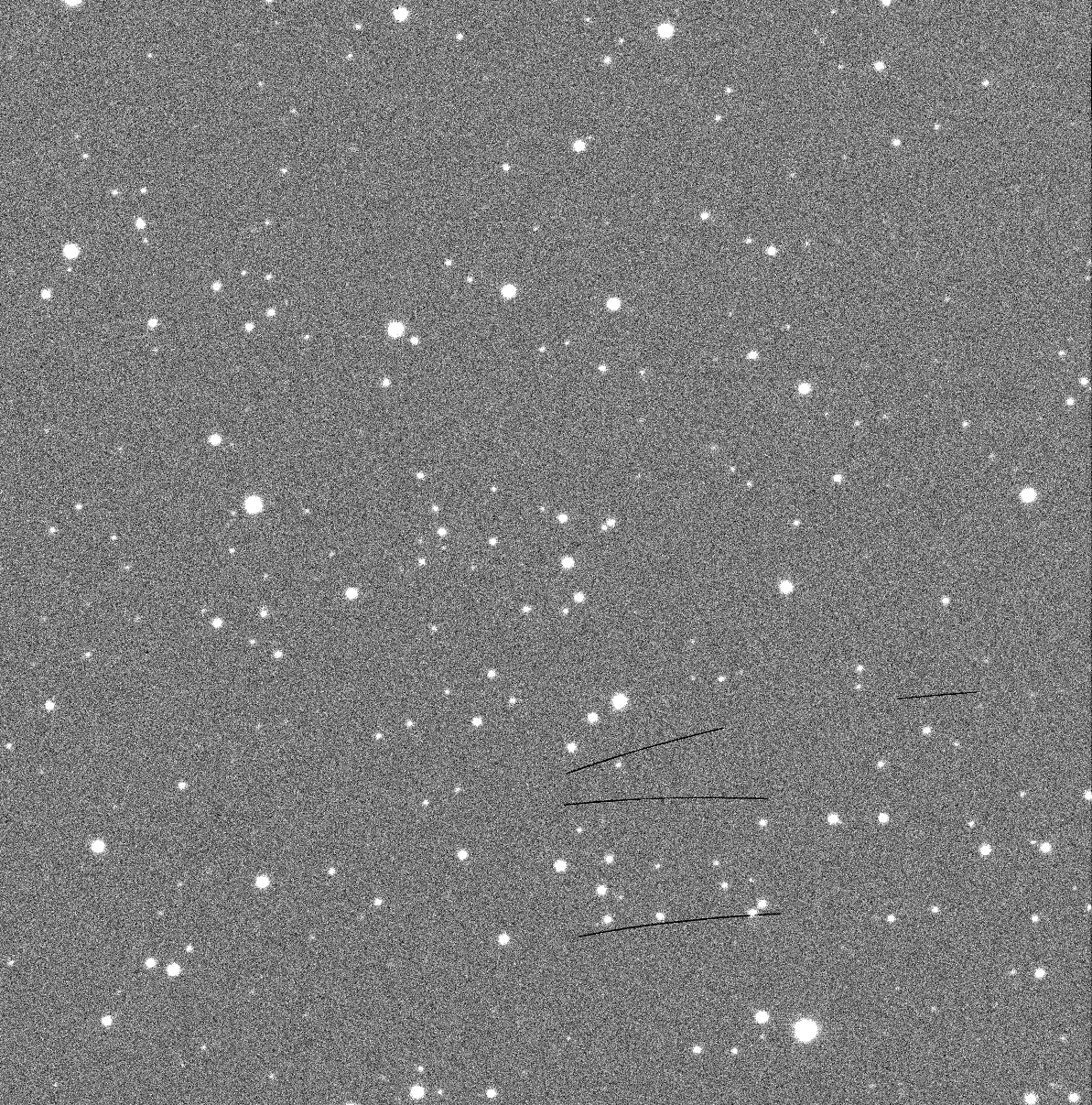

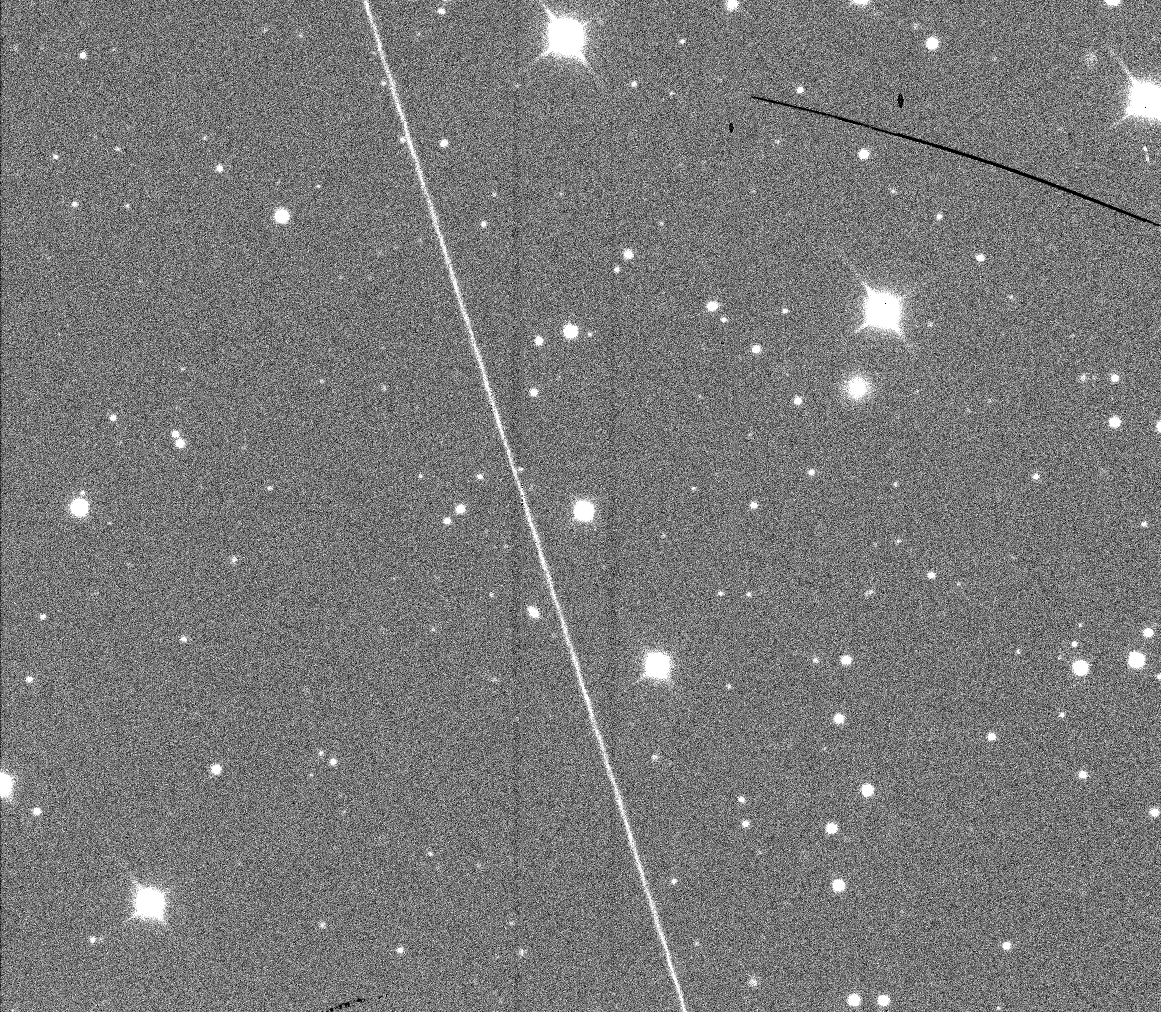

Thinking about how ‘glitch’ artifacts appear in astronomy images, both in image processing, and as satellites. These are a series of images from navigating around the different layers of Sky Viewer to capture signal and noise, and track substance and absence in both the sky that is being depicted and the process of mapping it.

SkyMapper

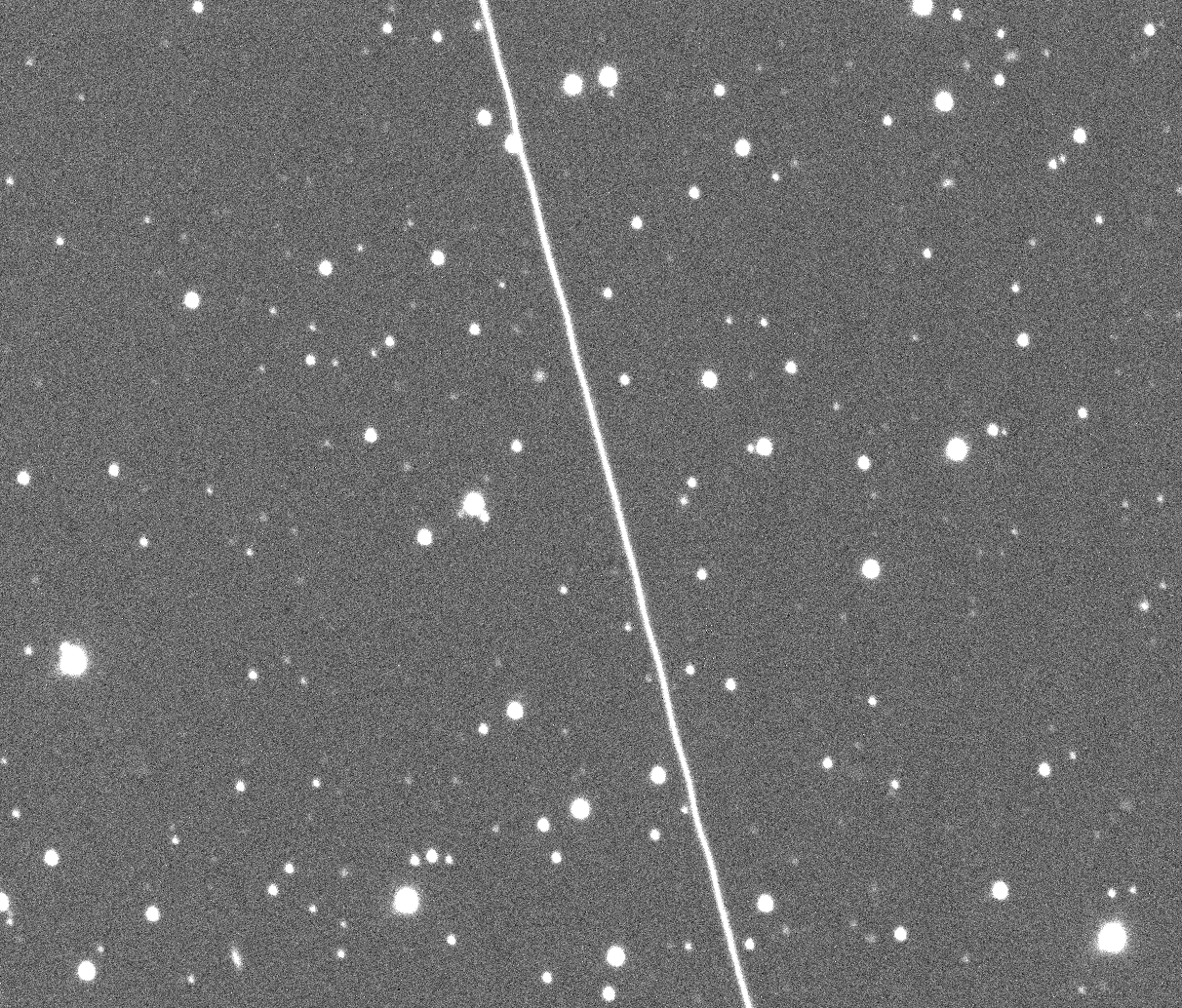

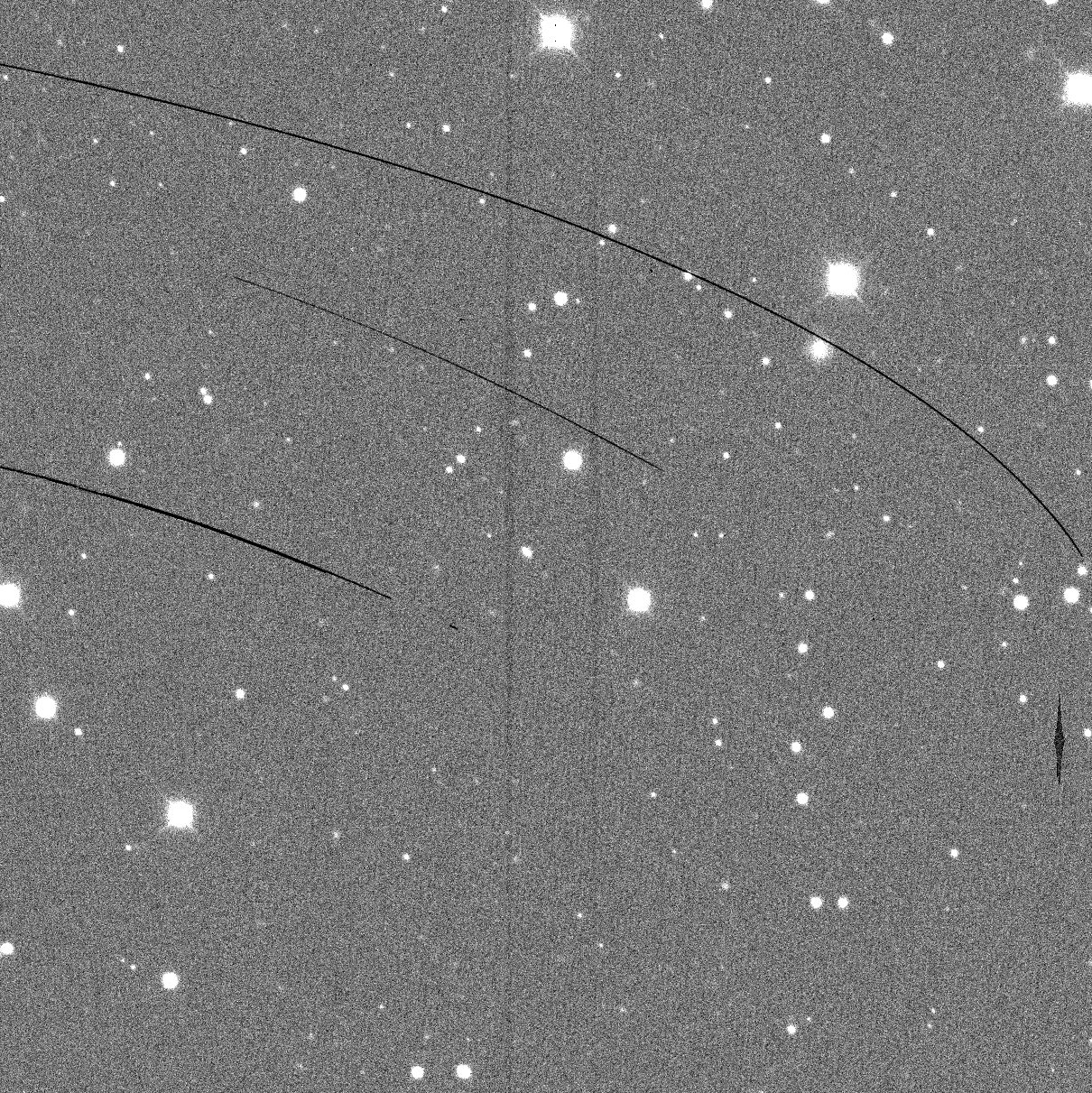

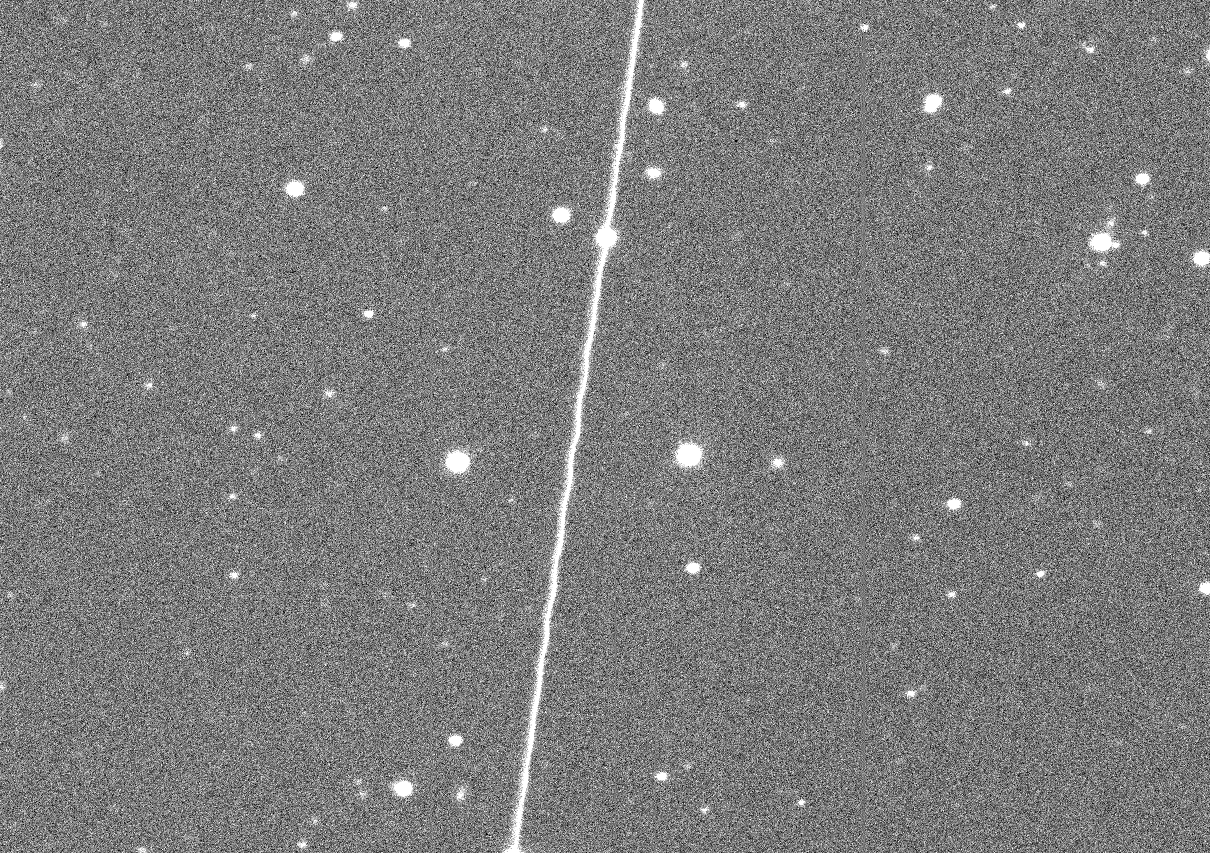

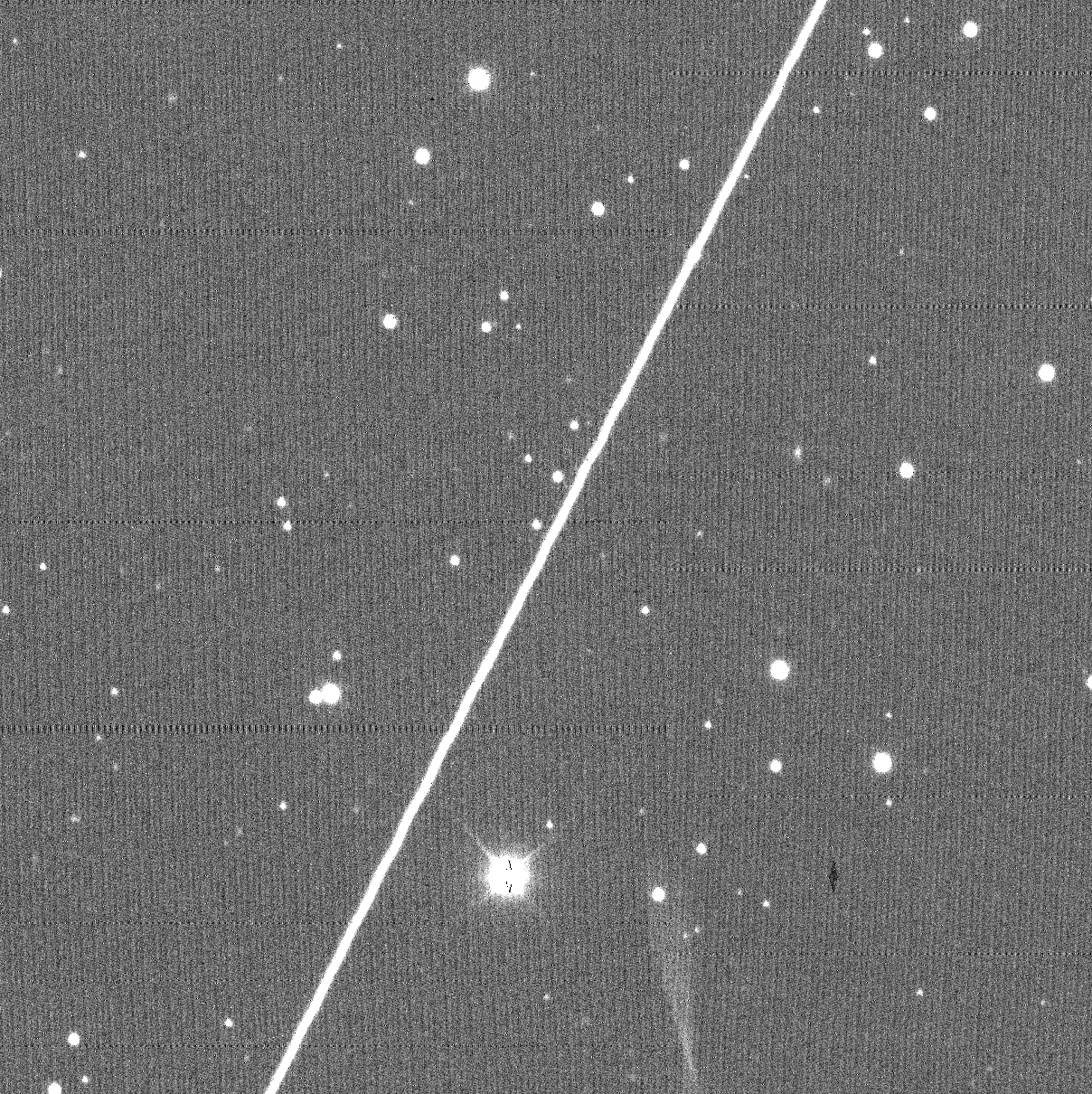

We have started using Skymapper, the wild-field survey telescope at ANU Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, to search out satellites that are already embedded in the database.

This telescope is at the summit of Mt Woorat (Siding Spring Mountain), in the Warrumbungle Dark Sky Park on Gamilaroi, Wiradjuri and Weilwan land.

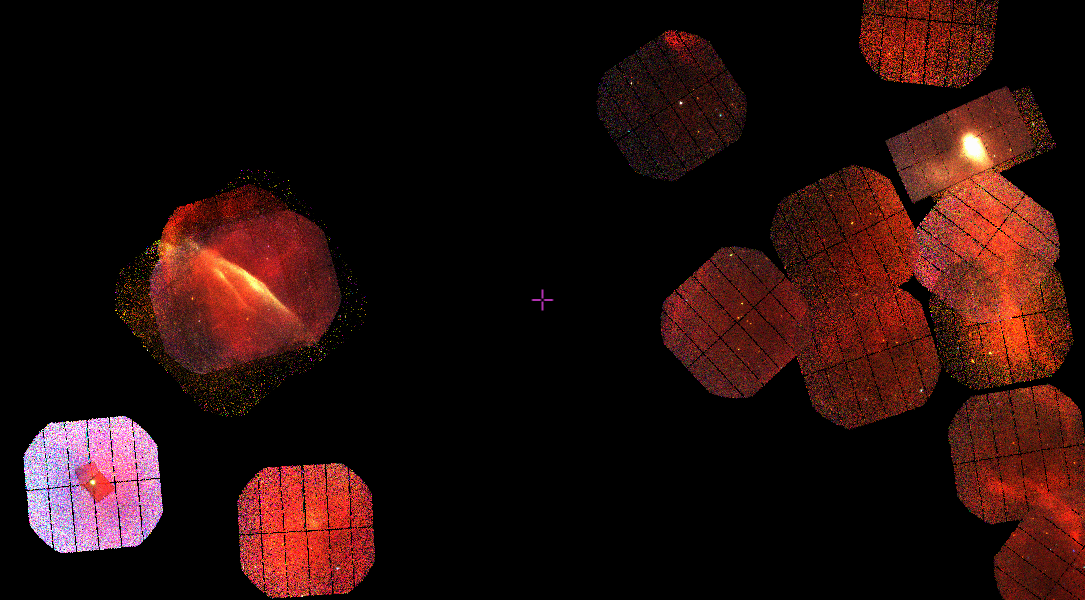

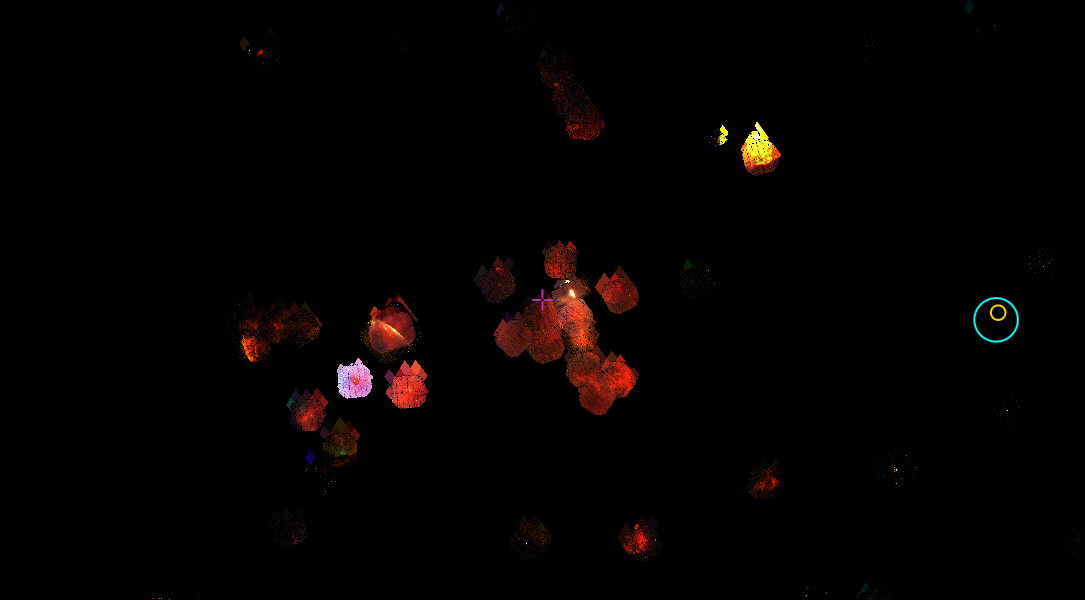

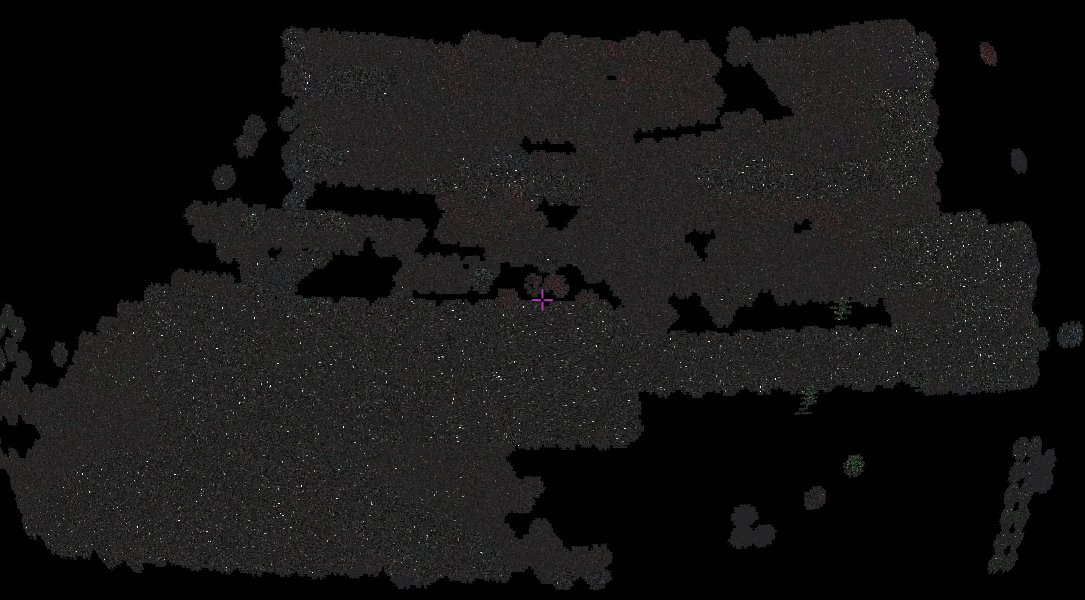

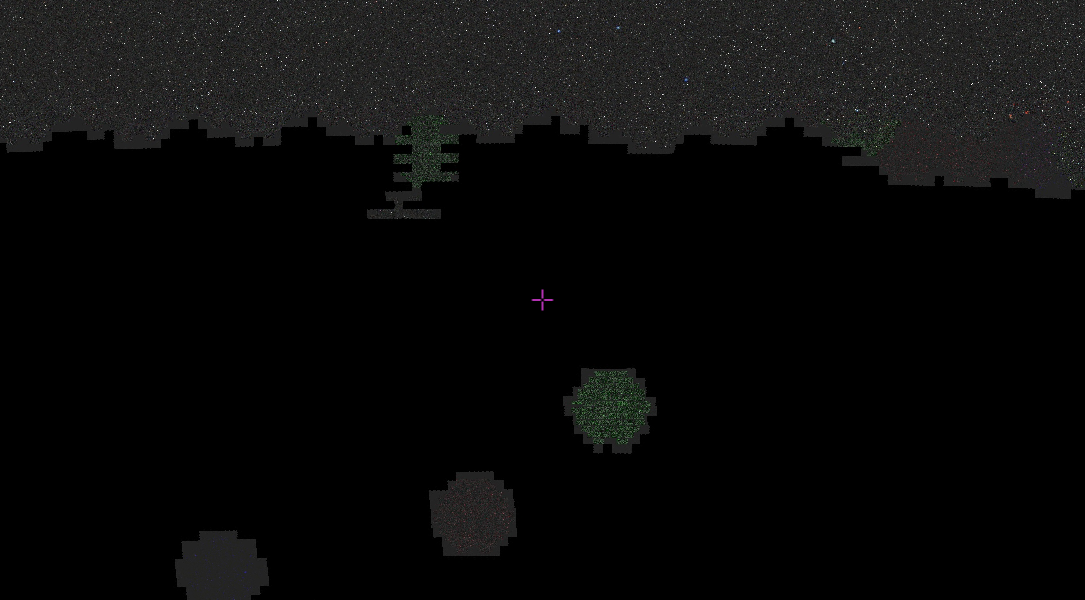

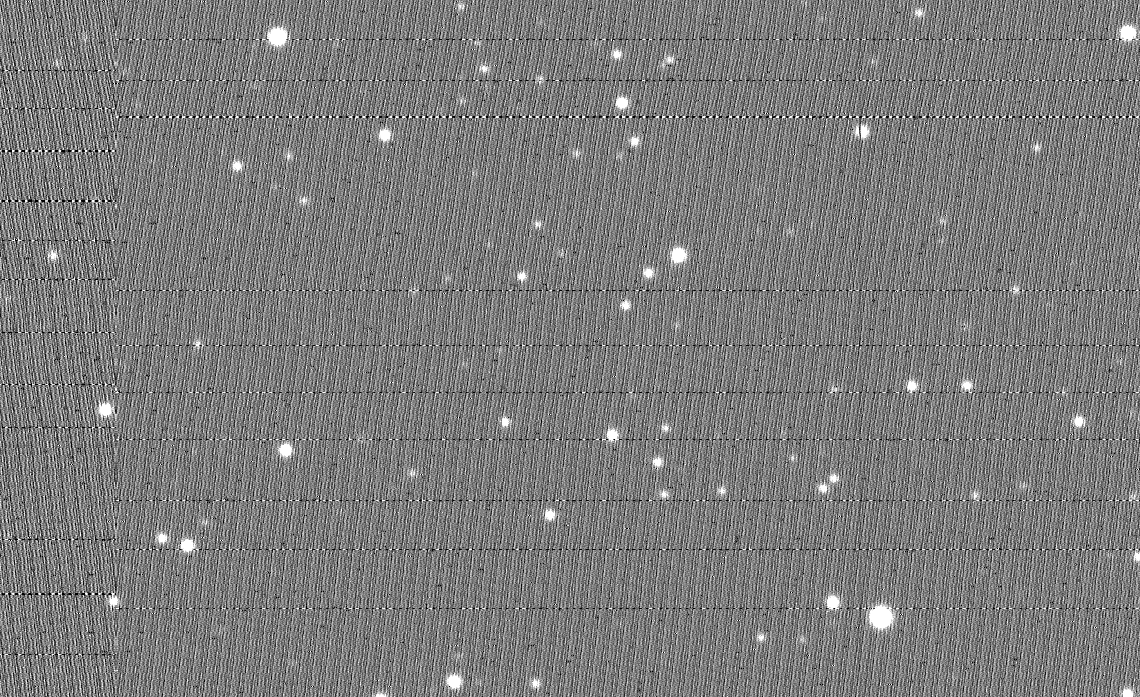

We discussed trying to access images that have been deleted due to too much interference but it isn’t clear where these go (yet!). So instead, Brad was able to find satellites by searching for images that are flagged as containing objects with significant elongation – this rules out stars, that are completely round.

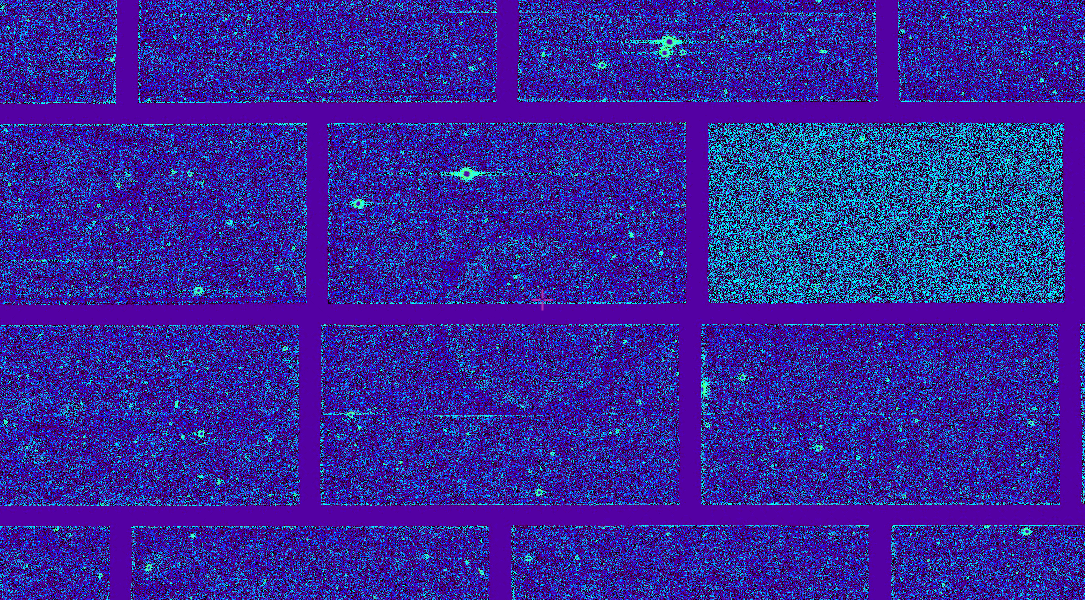

These images are examples of the results. They still pass as usable because they are image cutouts, only affecting a small section of a bigger view.

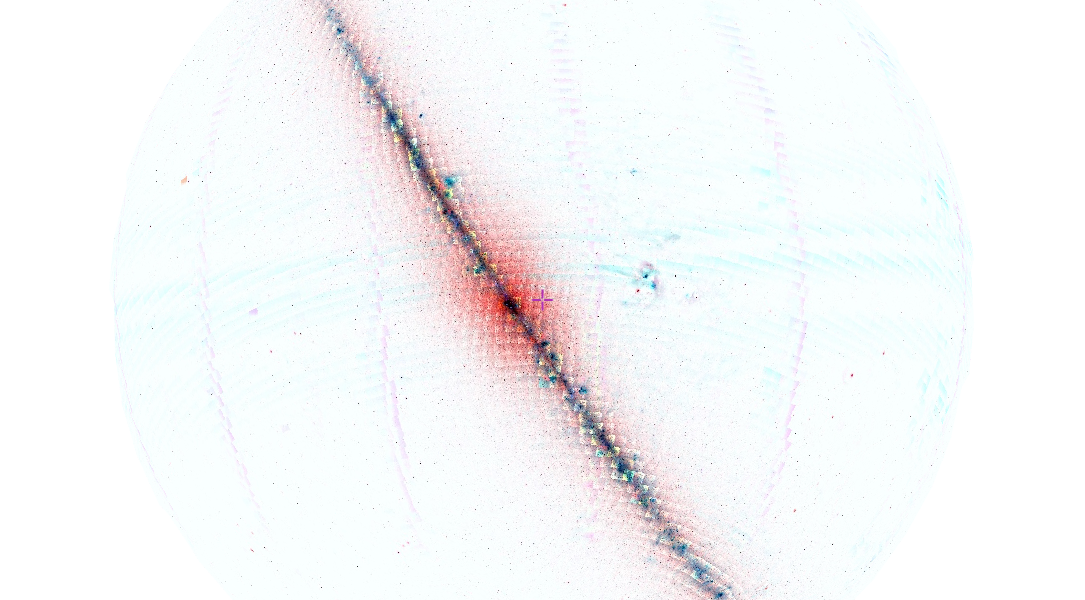

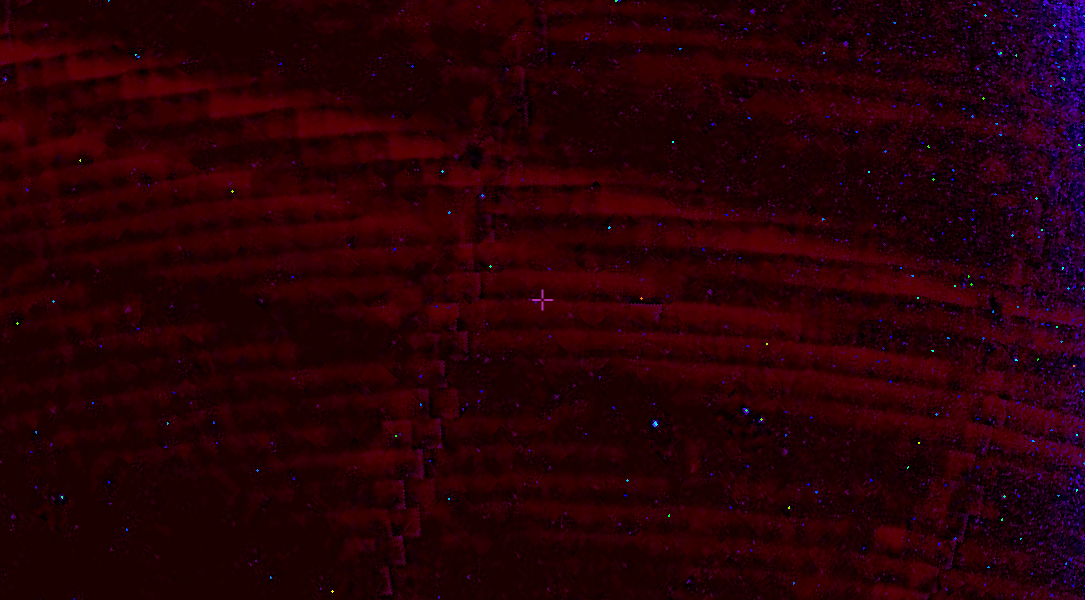

The ‘band’ of the images indicates the colour of light that is captured: U (ultraviolet); B (blue); G (green); V (visual); R (red); I (infrared) – but this measures intensity, not visual colour. In radio astronomy, this intensity is shown in contours, not physical images.

The different bands are captured in separated exposures of the same area. The variation is sometimes subtle but sometimes extreme, where prominent stars are the only consistent points. To compare the bands in a slightly different way, I have compiled a series of images of multiple bands describing the same area into an animated image sequence:

This is the same idea, but uses the Skyviewer service on Skymapper:

Finally, I experimented with animating and drawing over the images with satellite streaks while thinking through webs and lines in space:

More on Sky Viewer soon!

Quiet Zones

My earlier post ended with the paradoxes that mega constellations are inextricably tied up in, and this web of entanglements has only grown since then. A humanities perspective of the technosphere – technology that operates at the scale of a geological phenomenon (Haff 2014, Gärdebo et al, 2017) is interesting here, alongside the science.

Gärdebo et al. describe how satellites are technologies that change the environment as well as creating new ways to sense and relate to and within it, so become engaged in a ‘simultaneous knowing and making of the world’. (Gärdebo et al., 2017, p. 45)

Made of rare earth metals, satellites immediately embody geopolitical asymmetries of material extraction and distribution:

“Looking at satellites – as interscalar vehicles of the geopolitics they represent, the imaginaries they provide and debris they become – suggests a double paradox central to how the technology provides meaning to the world through expansion of its matter and vice versa.” (Gärdebo et al., 2017, p. 49)

The materiality of the space debri found in Dalgety stood out to me as a jarring friction of worlds: a futuristic (albeit charred) piece of technology driven literally colliding the vast land (albeit cultivated) traditionally owned by the Thaua and Ngarigo Aboriginal people of south-east Australia, a striking reminder of the direct trajectory of colonisation from Earth into space.

Hedley Twidle writes about these tensions in the similarly complex landscape of Karoo, South Africa, one of the sites designated for Square Kilometre Array (SKA), with the second site situated in remote Western Australia on the ancestral lands of the Wajarri Yamaji people.

Twidle pinpoints a significant paradox of observatories – and their utopian ideals – being situated at sites free of technological ‘noise’, which are also usually remote locations, small populations and ‘economic quietness’.

But such locations, precisely because they haven’t been invaded by technology, also often hold significant history of human civilisation of a different time scale. Twidle writes:

“In a world in which radio quietness has become a scarce resource, the SKA core site was chosen for its distance from the petrol engines, mobile phones, lighting and countless other technologies that produce radio interference: a space ‘empty’ of the electromagnetic noise of modernity and yet full of petroglyphs and stone tool middens: remnants of a different kind of modernity, in the archaeological sense, and which testify to an enormous time-depth of human occupation.” (Twidle, 2019, p. 786)

Observatories like this go to extreme effort in their design and practice to avoid interference from their own technologies. This representational challenge of radio astronomy, that involves ‘slow distillation and incremental layering of the faintest of sky signals’ rather than immediately conjuring up an image of the ‘sublime’, plays into this mismatch (Twidle, 2019, p. 779).

Radio astronomy involves capturing frequencies of light to indicate the elements of distant celestial objects. Several layers of data are then transmitted, cleaned, processed and intricately composited to form the images of outer space we are more familiar with.

When a satellite gets in the way, it becomes embedded within these layered signals of light and deep time, in a process rooted in physical place directly linked to a more recent – but just as unconfronted – past. What other signals are at play here?

Twidle distinguishes a difference between the science and humanities perspectives on this topic. Where science attempts to filter out the earthly noise to avoid seeing our own interference in images it creates, the humanities foregrounds aspects of the environment and industrial structures that force astronomy to the remote locations it needs to operate from (Twidle, 2019, p. 790).

I will be keeping this in mind as I combine these two approaches in this project.

References

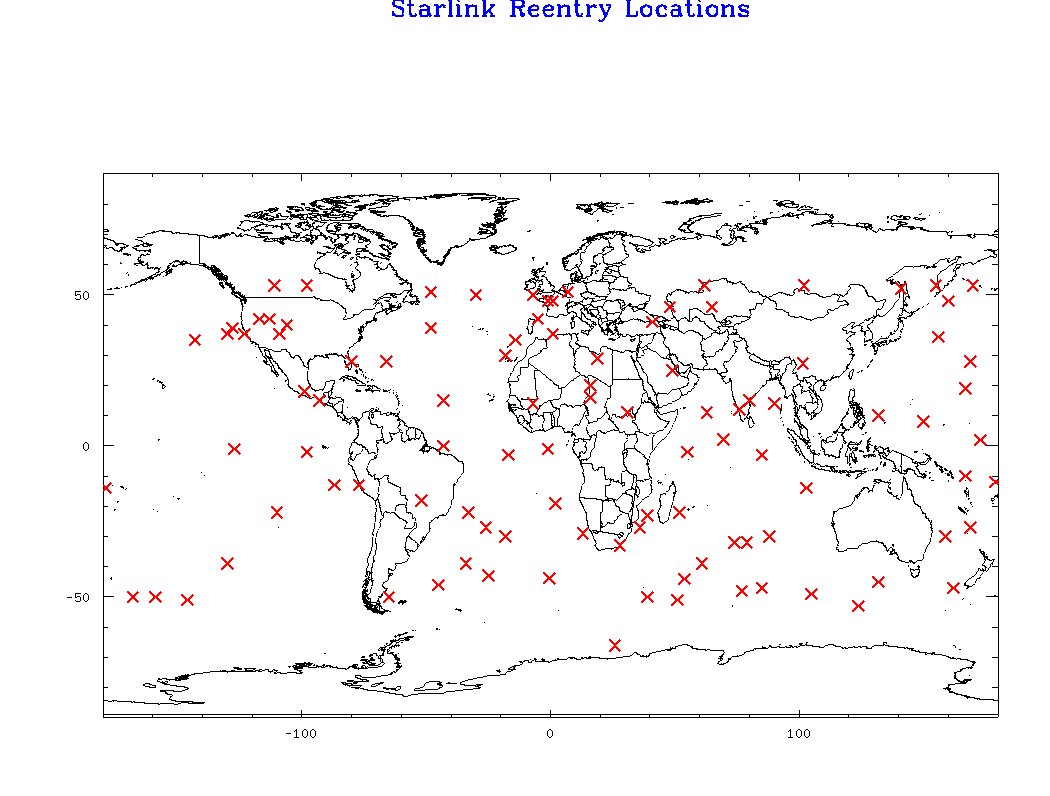

Space debris in Dalgety

Our aim to capture images of satellites deliberately – rather than by accident – is proving harder than expected so while waiting for a good weather window and the right opportunity for this observation I have been researching more about some of the issues mentioned in my last blog post, while Brad deals with space debris falling from the sky: